Editor’s Desk: Homeless criminalization is ‘blatantly cruel,’ ‘accomplishes nothing’

Eviction notice posted at East Wheeling encampment, Photo courtesy of Nathan Jobalia and The Hudson Editorial

Wheeling City Council’s decision to begin evicting residents of the East Wheeling encampment initially was announced to local service providers via email, lacking an explanation for such a radical and seemingly sudden shift in priorities.

Especially considering the Friendly City’s role in relocating many individuals into the East Wheeling camp over the past year, a potential justification for taking such drastic and destructive action was—and still is—difficult to imagine.

Some local media stories about the encampment and looming camping ban featured a report from the Wheeling Police Department which claims that 40% of crimes committed in the city over summer were committed by people experiencing homelessness. However, the referenced report blatantly misrepresents the most prominent statistic cited by some as an attempt to justify eviction of encampments and the ban on public camping.

The report itself admits that its usages of terms such as “situationally homeless” are “not meant to match exactly a dictionary definition.”

The report defines “situationally homeless” as “[consisting] of individuals that by actions or associations may be mistaken for homeless by the general public” as well as “[referring] to an individual that does have an address but chooses to frequent homeless camps or associate with homeless individuals regularly.”

The definition created by the police department for their report changes entirely which groups of people can be considered “situationally homeless.” Advocacy organizations generally use “situational homelessness” interchangeably with “transitional homelessness,” which refers to a temporary state of homelessness resulting from a major life change such as divorce, medical condition, job loss or other catastrophic events.

The claim that 40% of crimes were committed by people experiencing homelessness is formed by combining the number of criminal charges against people experiencing homelessness with the number of criminal charges against individuals categorized under the police department’s unique and misleading definition of “situationally homeless.”

The more honest and insightful takeaway from the report is that over the time period being examined, just 39 of 294 arrests, or 13%, involved a person experiencing homelessness. This roughly amounts to one arrest of a person experiencing homelessness every two-and-a-half days over the course of three months.

Shutting down the East Wheeling encampment—whether for false fears of rampant crime or otherwise—inevitably was going to cause incalculable devastation for many people in our community who have done nothing wrong—and who already were making a clear effort to exist within the guidelines initially communicated to them by the city.

Residents deserve much better than to be forced to abandon the one encampment they were made to believe would remain secure, especially while having no clear alternative sites to relocate to, and no plan of action from the city to support them in doing so.

Per the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty’s 2019 report on Ending Criminalization of Homelessness in the U.S., homeless encampment evictions reliably produce primarily harmful, dangerous and undesired outcomes, both for directly impacted individuals as well as for the broader community.

“Cities have relied on camping bans to authorize evictions of homeless encampments of all sizes, often with little or no advance notice,” the report states. “These evictions, or homeless ‘sweeps,’ not only displace homeless people from public space, but they often result in the loss or destruction of homeless people’s few possessions. The loss of these items can be devastating, as homeless people affected by sweeps often lose survival gear, identification and other important legal documents, medications, and irreplaceable mementos (…) These losses can cost a person their last remaining possessions, their dignity, or even their lives.”

The report states that sweeps generally are conducted by governments that have neglected to develop a plan to shelter displaced individuals who have no other practical options.

“Instead, homeless people are merely dispersed to different public places, leading to the inevitable reappearance of outdoor encampments,” the report states. “Displacement also disrupts homeless people’s access to social and health services, leading to worsened health and lapsed benefits. Sweeps can also cause the loss of employment or even access to available housing—the very things that people need to avoid ‘camping’ outside in the first place.”

The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness takes a similarly firm stance.

A 2015 report from the Interagency Council on Homelessness, entitled “Ending Homelessness for People Living in Encampments,” explains that “forced dispersal of people from encampment settings is not an appropriate solution or strategy [and] accomplishes nothing toward the goal of linking people to permanent housing opportunities, and can make it more difficult to provide lasting solutions to people who have been sleeping and living in the encampment.”

Put simply, the city’s shutting down of the East Wheeling encampment and its forced evictions of dozens of residents who were not provided with any practical alternatives has been wholly unnecessary, senselessly destructive and totally unjustifiable.

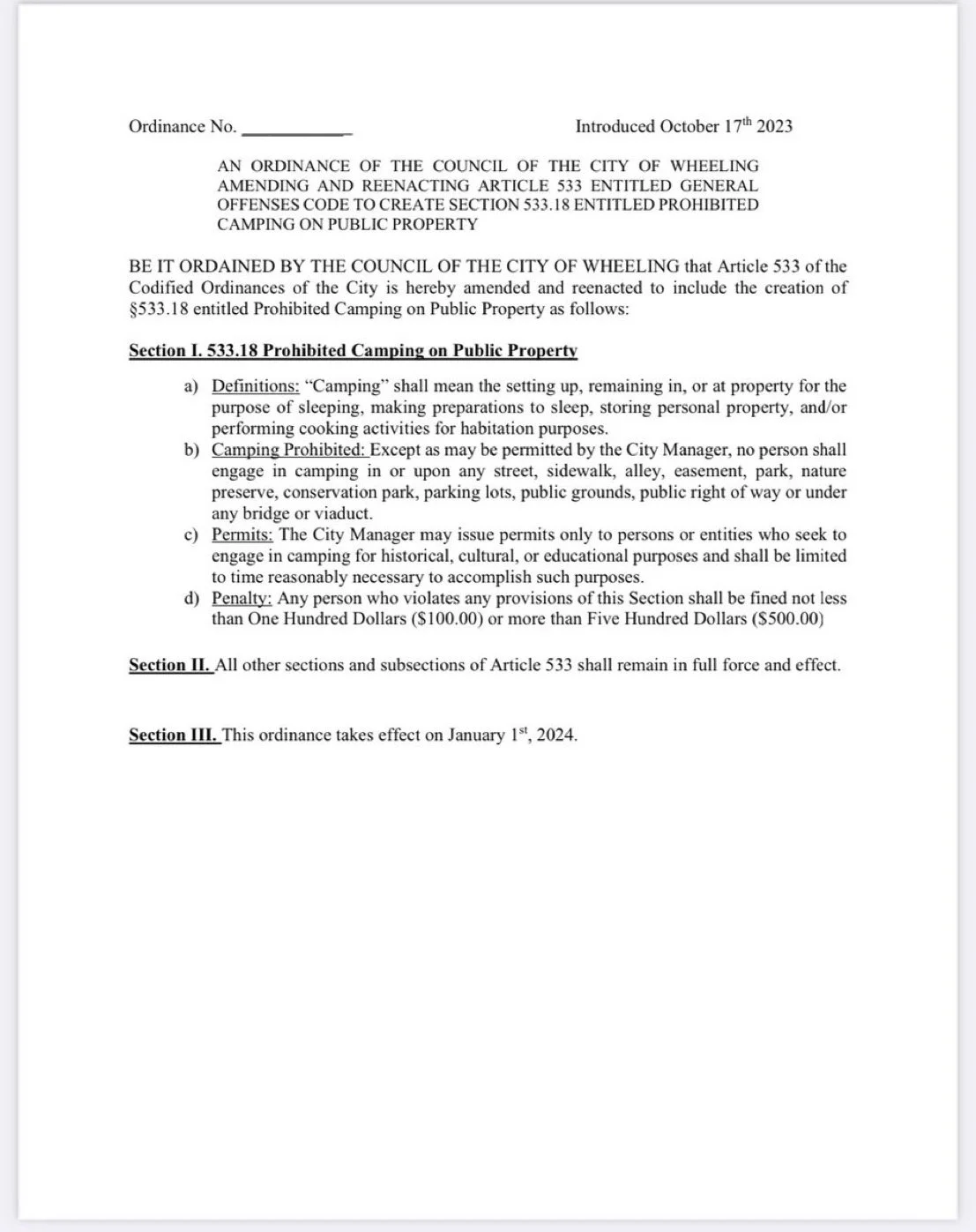

From the beginning, this reality has been obvious: Adopting a likely unconstitutional camping ban inspired by Parkersburg’s ordinance can only exacerbate the most dangerous and undesirable aspects of the city’s issues with homelessness, further complicating the prospect of any potential solutions moving forward.

While some local organizations do offer limited temporary or emergency shelter, the total number of beds available for those in need in Wheeling remains well below 100. Even a relatively conservative estimate of Wheeling’s homeless population likely would amount to at least three-times the number of total beds available. Many shelters also enforce strict barriers preventing most individuals experiencing homelessness from qualifying.

Each person in our community whose existence essentially has now been criminalized by our city council is someone who is struggling to make ends meet and who has no access to alternative shelter, leaving them no other choice than to sleep outside or in an unsafe abandoned building.

The American Civil Liberties Union of West Virginia provided Mustard Seed Mountain the following statement regarding cities’ attempts to criminalize homelessness:

“We encourage officials to fight poverty, not poor people. We oppose any efforts to criminalize poverty. Burying struggling people in more fines and fees is not only counterproductive, it’s blatantly cruel.”

A report from the Interagency Council on Homelessness published in 2022, entitled “Collaborate, Don’t Criminalize: How Communities Can Effectively and Humanely Address Homelessness,” indicates that attempts to criminalize homelessness are becoming more common in U.S. cities.

According to the report, the most effective way cities can respond to issues involving homelessness is to prioritize plans and actions that will “result in fewer tents, more people in homes, and more cost savings—[starting] with collaboration, not criminalization.”

The report states that effective responses to the public health and housing crises perpetuating homelessness must involve in policymaking people experiencing homelessness, and must focus on guaranteeing housing and other forms of support such as health care, job training, and education.

“While laws that criminalize homelessness have long been in existence, recent years have witnessed many states and communities across the United States enacting laws that fine and arrest people for doing activities in public that are otherwise legal in the setting of a home: sleeping, sitting, eating, drinking,” the report states. “These policies are ineffective, expensive, and actually worsen the tragedy of homelessness. There is a better way to respond to this crisis.”